The Problem with Feel-Good Environmentalism

It’s time to stop confusing moral purity with effectiveness.

I hosted a “zero-waste” dinner for a half a dozen other climate activists at my apartment back in 2019, when I was still deeply entrenched in the climate movement. Eight of us squeezed around my table, munching on locally sourced veggies, when I brought up a fact I’d recently discovered while producing a video on New York City’s plastic bag ban: plastic bags have a lower carbon footprint than paper.

I mentioned it casually, but the reaction was a collective cringe. I was met with looks that said, “Why are you bringing this up?” and “So what?” An unspoken “Your point is?” hung in the air.

There was no curiosity, no exchange of ideas, no conversation. The response wasn’t outwardly hostile, just flat—a dud.

At the time, I wasn’t confident enough to hold opinions that differed from the climate activist groupthink. Their silence told me I’d said something wrong, that I’d stepped out of line. I felt my energy shrink and a pit form in my stomach. The conversation turned to something else, but I felt stuck in anxiety, regretting I’d brought up the fact at all.

After everyone left, I replayed the moment over and over in my head. Why had I said that? Would they think I wasn’t a true environmentalist? Was I showing I didn’t belong? Was I too privileged to be part of the movement?

You might think that’s a dramatic reaction to a brief, awkward moment, and you’d be right. But that’s what it’s like when your opinions come entirely from the group. At that time, I was so embedded in the climate groupthink that every opinion I held passed through collective approval first.

When I came across a fact that contradicted the group consensus—in this case, that plastic wasn’t inherently bad for the environment—acknowledging the contradiction made me feel unsafe. My worldview was built on sand: the fragile approval of others. When I stepped outside of the safety of groupthink, my inner world collapsed, and anxiety and self-doubt filled the void.

Former environmental activist Michael Shellenberger has written about how the environmental movement has taken on a kind of religious dogma—that many followers don’t treat it as scientific inquiry but as a faith to be preached. That was my experience exactly. Among activists, I rarely felt free to ask questions or express doubt. Certain beliefs were simply taken for granted: that veganism was morally superior, that fossil fuels were evil, that solar and wind would save the planet, and that America was to blame for it all.

It wasn’t until years later, after I’d left the movement, that I realized what had really happened. I hadn’t said anything wrong that night. I’d merely questioned one of the movement’s sacred tenets: “plastic is bad.”

The problem with the modern climate movement is that it’s not a genuine search for truth or solutions. It’s a moral code imbued with what I call feel-goodism, the belief that emotional or moral satisfaction equals effectiveness.

It’s feel-goodism in action when we insist on recycling low-grade plastics that can’t actually be reused and end up polluting rivers in developing countries. It’s feel-goodism when we demonize natural gas, even though it emits 50 percent less carbon dioxide than coal. It’s feel-goodism when we glorify “green” technologies like wind and solar, and ignore trade-offs like intermittency. It’s feel-goodism when we put electric vehicles on a pedestal while ignoring the environmental destruction in China and the Congo from rare-earth minerals mining.

Feel-goodism makes you feel good, right, and virtuous, but those feelings don’t translate to effective environmentalism. What’s left is a climate movement that puts performative acts above complexity. As long as we’re recycling, opposing fossil fuels, and cheering for renewables, we belong, we feel good, and we’re good environmentalists.

But belonging isn’t the same as progress.

As someone who once believed in these moral absolutes, I now see how dangerous they are. Real solutions require nuance. They demand uncomfortable trade-offs and the courage to champion what works, even when it’s unpopular.

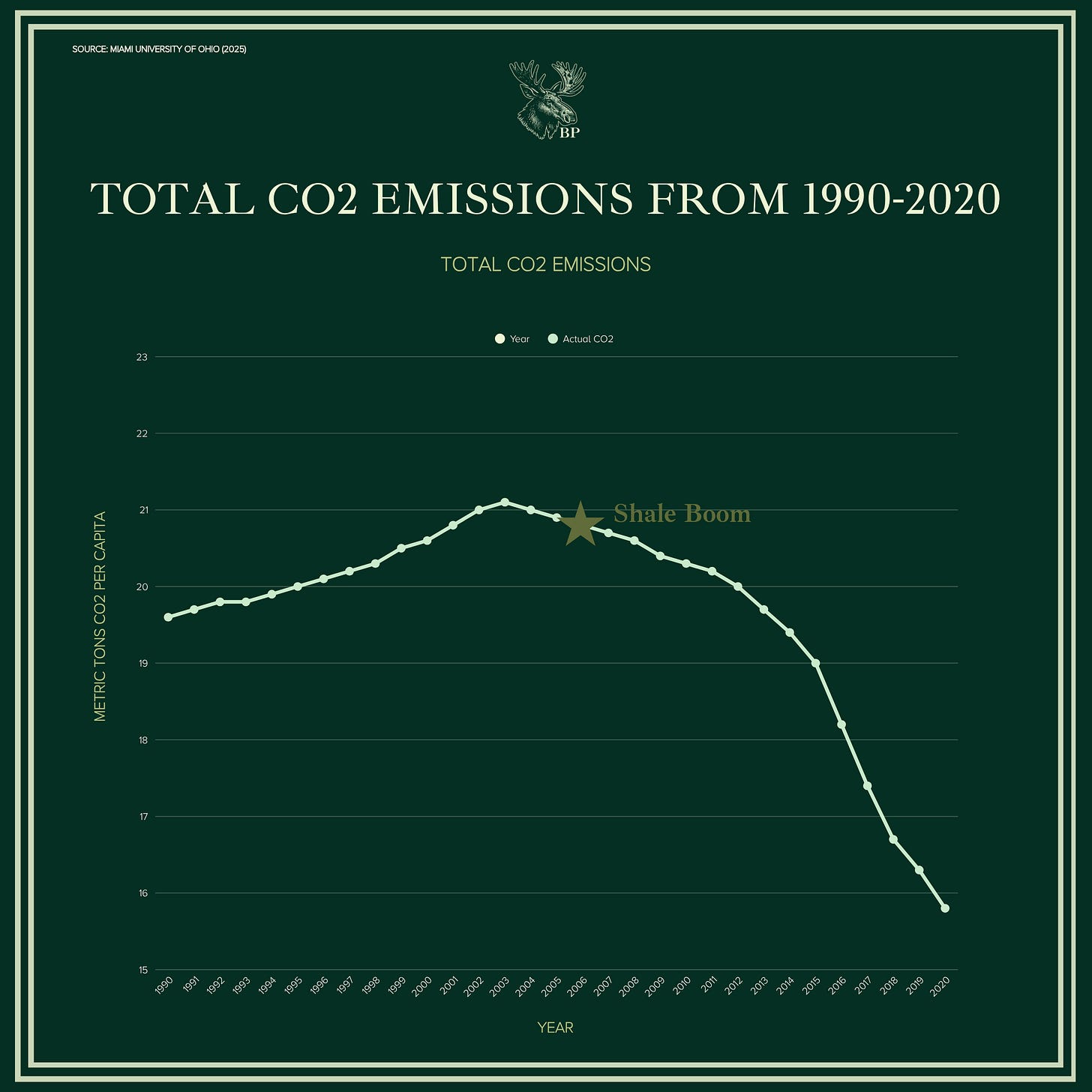

Natural gas, for instance, has been the single biggest driver of carbon reductions in the U.S. It’s affordable, abundant, and much cleaner than coal. Fossil fuels, more broadly, have lifted billions of people out of poverty and should be used more to help developing nations that deserve the same chance at prosperity that we in the West enjoy.

Does that stance make you popular in environmental circles? No. But it’s honest, and it’s rooted in reality, not righteousness.

If the climate movement could let go of its feel-goodism and focus on results, we could make real progress and I think bring more people to our cause, by championing human prosperity and protecting the planet.

That means working across the aisle, embracing compromise, and learning from groups like the American Conservation Coalition, whose advocacy arm has helped pass bipartisan conservation and climate legislation.

It’s time to stop confusing moral purity with effectiveness. If we can do that, the environmental movement might actually save the world, not just make us feel good about trying.

Lucy Biggers is a former climate activist turned anti-climate alarmism creator. She is the creator of a viral video series, “Calming Climate Charts,” that counters some of the scariest misconceptions about climate change. At her day job, she is the Head of Social Media for The Free Press.

I’ve worked in corporate sustainability for almost 10 years- I couldn’t agree with this more. Thanks for saying this so well

Plastics are generally bad in other ways. The proliferation and ubiquity of microplastic contaminants is a big one. It doesn’t help that virtually everything comes wrapped in plastic these days since, as you note, recycling of plastic is largely a joke.

I absolutely agree with your overall points though. There is a nuance and complexity to so many of these issues, but the attention economy has no patience for it and people choose the “feel good” option because it’s easy and they want it to be true. It makes it hard to have a substantive discussion about how many of the perceived risks of climate change (a Mad Max uninhabitable Earth) are not actual risks. It makes trying to consider and mitigate the actual risks much more difficult.