Reindustrialization Requires Energy Dominance

It’s not enough to prioritize energy production and export leadership alone.

Once the dream of a select group of policy wonks and hard-tech innovators, reindustrialization is now an explicit aim of American national policy. President Trump has made it a central economic objective in his second term, declaring in his inaugural address that “America will be a manufacturing nation once again.” President Trump is just the most prominent of a growing number of leaders who understand that industrial power underwrites economic resiliency, broad-based prosperity, and national security. Reindustrialization promises to restore vital economic assets and capacities that American policymakers in the past allowed to drift offshore, but it will not be an easy task.

Achieving reindustrialization will require public financing, private initiative, and the development of onshore supply chains the likes of which American manufacturers have not seen since the Cold War. Industrial policies, including subsidies, loan guarantees, and trade barriers, can bolster infant industries, rebuild decrepit production lines, and promote strategic sectors, such as advanced electronics. But these measures can only go so far and will not ensure the long-run competitiveness of American industry. Reindustrialization is only possible if we have the energy to power new factories and will only thrive in the long run if American energy is stable, sovereign, and secure. Absent the energy to sustain new industrial production, public investment would be wasteful.

America’s manufacturing sector, once the world’s factory, was built on the cheap and abundant energy that coal and petroleum provided in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Losing that advantage in the 1970s cost American industry its competitive edge and precipitated its long decline. Among many other factors, China’s current industrial dominance relies on the country’s abundant energy production, massive investments in energy infrastructure, and extremely low and stable prices that reduce operating costs for manufacturers.

Reversing decades of industrial decay will increase America’s total energy consumption in the near term. Increased consumption will demand more energy production and distribution. The success of reindustrialization will depend on low energy costs, based on a secure and abundant energy supply, with price stability guaranteed by American leadership in global energy markets and efficiency gains driven by energy technology innovation. In brief, reindustrialization requires energy dominance.

Industry, by nature, is energy intensive. In 2024, the industrial sector—which includes manufacturing, mining, construction, and farming—accounted for 35 percent of all U.S. energy consumption, second only to transportation. Even after decades of decline, manufacturing takes up three-quarters of industrial energy use and approximately a quarter of all U.S. energy consumption, more than the residential or commercial sectors. While efficiency improvements have slashed the energy needed per dollar of output, even lower-end manufacturing requires an enormous amount of energy. The U.S. food industry, for example, consumes as much energy as one-eighth of all residences in America. Advanced manufacturing, the priority of most reindustrialists, requires enormous amounts of electricity. A single large chip factory can consume as much energy as an entire town.

Industry’s share of energy consumption is so massive that, since the 1990s, declining industrial demand offset any rise in nationwide consumption until the data center boom. Reversing the decline in manufacturing means reversing that decline in the sector’s energy consumption, and in turn, increasing demand for all the resources in the diverse basket of energy sources that power American industry.

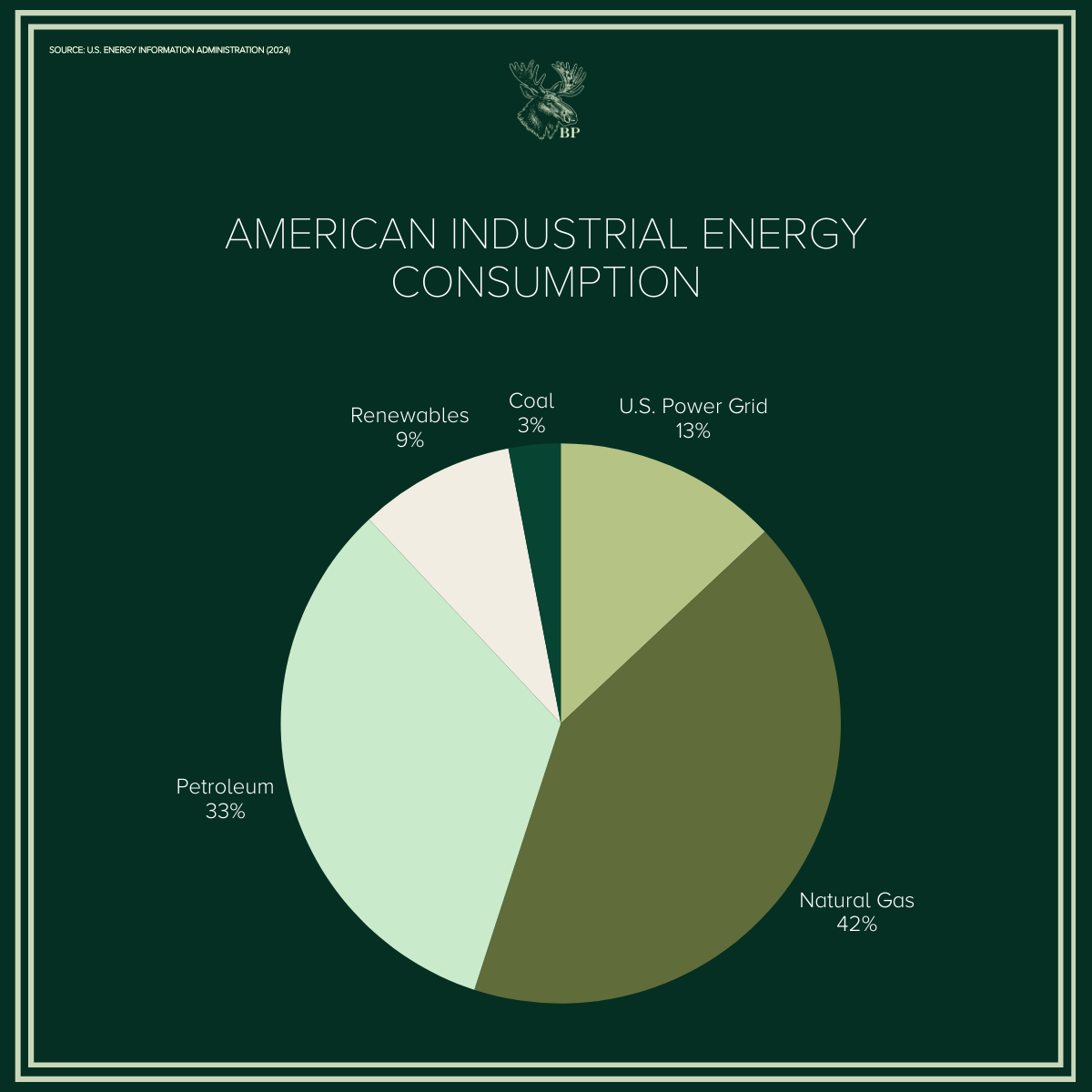

Large-scale manufacturing facilities require not only far more energy than homes or even data centers but a more complex blend of energy as well. Only 13 percent of all industrial energy consumption comes from the power grid, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. The remainder is a blend of sources including natural gas (42 percent), petroleum (33 percent), renewables (9 percent), and coal (3 percent). Much of this consumption directly fuels industrial production, providing heat and mechanical energy used in manufacturing. Even though new “clean” industrial plants may use more electricity than their predecessors, manufacturers lean heavily towards the use of hydrocarbon fuels.

Advances in small modular reactors, geothermal power, and solar heating may someday soon efficiently supply heat and mechanical energy to factories. In the near term, though, policymakers must meet manufacturers where they are and ensure they have access to the hydrocarbon fuels they use. Petroleum is also an essential feedstock for the chemical and plastics industries, which turn the energy source directly into their products. Barring fundamental breakthroughs in chemistry, hydrocarbon production will remain essential for industrial production.

Reindustrialization demands low prices and expanded supply across the entire industrial energy mix. Abundant natural gas, baseload power from nuclear and hydro, low oil prices, cheap American-made solar panels, even “beautiful clean coal”—industry needs all of the above. High or volatile energy prices, for any source, pose a much greater threat to industry than to household budgets and most commercial balance sheets. Variable operating costs at a factory can make the difference between its profitability and closure.

The history of deindustrialization makes industry’s vulnerability to energy costs painfully clear. In the 1960s and early ’70s, American heavy manufacturing, such as our world-dominant steel and automotive sectors, held its own against foreign competitors who benefitted from cheaper labor and government subsidies. It was only when the 1973 oil crisis spiked all energy costs by 56 percent in a single year that these industries became uncompetitive, factories began to close, and production moved overseas. Another oil crisis in 1979 made matters worse, and after that point, industrial employment never recovered.

The oil crises of the 1970s also help illustrate why “restoring American energy dominance […] and reshoring the necessary key energy components is a top strategic priority,” in the words of the excellent 2025 National Security Strategy, published in November. At the time of the 1973 oil crisis, America imported over a third of its oil, becoming dependent on unreliable foreign suppliers, particularly in the Middle East. When these suppliers embargoed the United States, Congress responded appropriately with a strategic infrastructure investment, passed a law accelerating construction of the trans-Alaska pipeline. Today, we must ensure American dominance in energy production and exports to protect our economy and industries from market manipulation by foreign rivals. Energy security forms the foundation upon which industrialists, innovators, and investors can revive American manufacturing.

It’s not enough to prioritize energy production and export leadership alone. The full-spectrum energy dominance that reindustrialization needs will also demand proactive policy to expand energy transmission, build energy industrial capacity, and reinvigorate American leadership in new energy technologies.

First, policymakers must allow the dramatic expansion of energy infrastructure through comprehensive permitting reform. This is perhaps the most ubiquitous energy policy recommendation in Washington, but for good reason. If we do not streamline the process for building pipelines, transmission lines, and nuclear plants, both energy dominance and reindustrialization will be impossible. Without sprawling permitting reform that establishes federal preemption for strategic infrastructure, like the legislation that paved the way for the trans-Alaska pipeline, we will struggle to meet data center demand growth and have no chance of powering numerous large-scale manufacturing plants.

Second, industrial policy must treat the energy industrial base with the same seriousness it applies to the defense industrial base and the semiconductor industry. The most obvious place to start is with infrastructural components. Gas turbines, transformers, batteries, grid equipment, and industrial power systems are strategic goods. Reliance on offshore production has already constrained availability during the current wave of high demand. Dependence on rivals may prove catastrophic in times of crisis. Production incentives like the Advanced Manufacturing Production Tax Credit are useful, but even more valuable are robust demand anchors, such as regulations requiring the use of domestically produced transmission equipment.

Third, federal programs must integrate R&D into the U.S. energy industrial base to scale domestic production and drive practical innovation. Manufacturing innovation happens in the industrial commons, “the collective operational capabilities that underpin new product and process development in the U.S. industrial sector.” A national ecosystem of energy manufacturers and researchers, supported by federal investment, will drive innovation and commercialization while anchoring them in domestic supply chains.

Reindustrialization and energy dominance are not separate tasks but two halves of the same project: restoring American economic power and resilience. Industrial policy can mobilize capital and talent, but only energy policy determines whether factories are built, can operate at scale, and remain competitive over time. The Trump administration’s ability to secure abundant, affordable, and reliable energy will determine the success of its reindustrialization agenda.

Daniel Bring is executive editor of American Affairs, a quarterly journal of public policy and political thought, and senior fellow at the Bull Moose Project. At American Affairs, Daniel directs research programs, events, and external relations, in addition to managing the journal’s Washington, D.C. office. At the Bull Moose Project, Daniel conducts research on supply chains, reshoring, and resource extraction. Daniel graduated from Dartmouth College with an A.B. in history.